The Invisible Labor of Motherhood: Confronting the Guilt Gap Between Men and Women

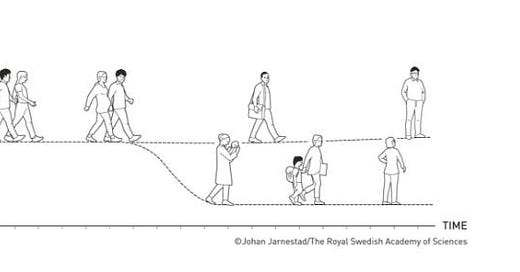

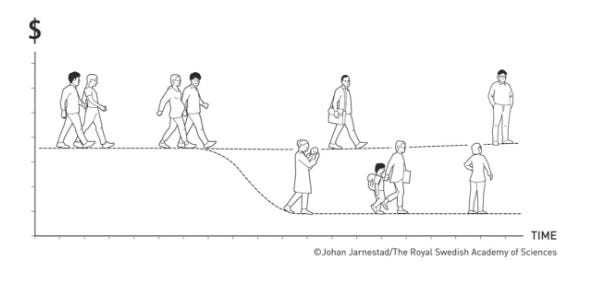

The guilt gap. Women, “anxious” and “exaggerated”, can you step to the side? Men, “comfortable and relaxed,” step in and do what feels uncomfortable. The gender pay gap, by Claudia Goldin.

Not so long ago, I wrote about the ‘invisible’ chores that men struggle to see, also in raising children. A reader sent me this message in response.

“I think sometimes it can also be on us women who make it so that men aren’t implicated. You end up thinking — ‘it’ll be quicker if I just do this, it’ll take just five minutes, since I know how to do it.’ And it’s important to say: ‘it doesn’t always have to be me. In fact, what would happen if I wasn’t here? We need to rethink this, together.’

The reader wasn’t putting the blame that men don’t do the work at the feet of women. No. Women aren’t to blame for the gender dynamics which disadvantage them. There is education and socialization that has predetermined gender roles for us since we were children.

It’s a classic, assuming that a certain job — getting the kids dressed, making plans, cleaning up — has to be done by one party, because the other one will always do it badly. Breaking this systemic inertia needs initiative and self-criticism from both parties.

A good start is asking ourselves several questions:

Why does one of us do the job better than the other? Do I have a natural talent for cleaning bathrooms? Why doesn’t the other one want to learn how to do that? And what’s behind it? A lack of trust? Reproducing co-dependency conditions? A rush of territorial control?

If what I do — remunerated work or knowing everything about my children — gives me a determined role and space in a relationship, what happens if I let it go? Can I become expendable, or less desirable?

I know there are men who clean the bathroom and take their kids to the playground or to get them vaccinated, but it’s not a rule. On a global level, women do 76.2% of all of the care work which is not remunerated, dedicating 3.2 times more time to these tasks than men, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

As an exercise, let’s ask ourselves: Who is researching, looking for, finding, choosing and closing the deal on a specialist, pediatrician or therapist to cover the range of needs at different stages of childhood? Who skips work when a child gets sick and can’t go to school? And why is it like this?

…

One thing is for sure: at this stage, many men have simply stopped reading (but #NotAllMen), and many women think that their partner should be reading this newsletter, but it’d bore them. Am I right?

…

Another reader pointed out something important: “It always takes a woman to start the change.” She was referring to the list of things to do to make a woman’s work more visible: “Proactivity is unidirectional.”

Why does change start with women?

Because we women were institutionalized with the tasks of care. Not only of children, but of everything that implies care: parents, relationships, homes, etc. We are ‘taught’ to detect what needs to be taken care of and to take care of it. It is possible to educate differently, yes, but it is not easy, it will take generations. A couple can share tasks. Everything is fine, until a child arrives and the added variables are many more than you could predict. And that's where the institutionalization or discipline comes in, where making that list is more visible to women. Sometimes it is difficult to explain each part of it or to teach the other to put it together. There is a little bit of unconscious relaxation of roles.

…

The issue of housework and caregiving becomes more complex when we look at the different feelings that surround the same situation.

“How many times have we been called 'exaggerated' or treated as 'anxious' for taking care of things that end up not getting done — unless we step in?” wondered

in Hartas, her newsletter.Sichel, a philosopher and mother of two, does not only refer to the care tasks or the mental load but to “something else”, something that “is like a feeling” that women have in the background and that accompanies them (and that does not happen to us men, or not so much).

“How many times have you wondered why he is able to go to work calmly when the baby has a fever, while when you are the one who has to leave, you are absolutely mortified, feeling like an abandoning mother?” she asks.

“It's not just executing the task or thinking about it. It's also that extra worry that those of us who are mothers suffer from. This difference in experiences has a name: guilt gap,” writes Sichel.

The “guilt gap” is a concept used by Pulitzer Prize-winning U.S. journalist Ellen Goodman, a former columnist for The Boston Globe and Washington Post, to describe “that gulf of worry that separates mothers from fathers.”

It is a way to describe the difference in emotional burden between men and women in caregiving. Women tend to take on more worries and responsibilities because that is what they have learned is expected of them, and that leads them to feel more guilty for not meeting certain standards. This extra self-demand can lead a woman to constantly seek information, educate and improve herself.

Sichel puts it very well:

The guilt gap is the one that makes us read more closely the package insert that tells us how much ibuprofen our child has to take in the early morning. The one that makes us buy the latest book on respectful parenting or listen to a podcast that helps us understand tantrums. It's the one that drives us to read more books, do more workshops and become experts on all topics.

This puts us mothers at a crossroads that is sometimes difficult to get out of. On the one hand, we feel the interest, commitment and responsibility because, as mothers, what could be better than to be in most of the care of our sons and daughters? On the other hand, however, it feeds back negatively into a circle in which we mothers seem to be the only ones who know what, how and when to care for our sons and daughters.

…

I wonder if the “guilt gap” could also be that which operates behind some comments I make. For example, when I appear confident and calm, even somewhat boastful while I say that my partner “sees problems in everything, she never relaxes, she is always worried”. It's not about who is right (no one is right) but about understanding why what happens happens.

In these five years in which our two children were born, I am the one who spent the most time with them and the one who, by far, did the least paid work. But there are things that “naturally” continue to be hers, as she is the one who is the main earner (nobody pays me for the care, obviously). Why is it Irene (and not me) who “thinks” of organizing the clothes that the kids have outgrown and see if we need something for the winter?

In that tension in front of “what to do”, the emotional gap appears: she worries about that issue and about a thousand others, because she somehow considers that it is up to her. Whereas I don't do it because I don't feel guilty, simply because I don't think I am at fault and I will eventually solve it when the time comes. The emotional approach to the same situation is quite different.

What is evident is the internalization of traditional gender roles, which make women feel more responsible for taking care of the family and the home, even though they work alongside their partners.

Sometimes, we men are comfortable and boast about not being like this or that jerk. We seem to think that it is enough to upload a photo on social networks with our children to show that we are loving, sensitive and committed.

Meanwhile, women have been part of the labor market for decades and, at the same time, they continue to do what they were already doing — caring and raising children. This is still expected of them, even though they have added to their lives the pressures of paid work in a scenario with unequal conditions, where we men continue to be the most favored. Yes, gender differences in employment are greater than previously thought, says the ILO.

These processes in the private sphere end up having an effect outside the domestic sphere as well: motherhood damages women's careers, but does not penalize men's professional development. A study published by The Economist points out that:

Millions of women have to quit their jobs or switch to another, reducing their hours to achieve a work-life balance with childbirth and childcare.

25% of women leave work one year after having their first child and 15% have not returned to work 10 years later.

…

No one explained the gender wage gap as clearly as the American Claudia Goldin, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics last year. A professor at Harvard University, she was recognized for her research contributions in analyzing women's wages and labor market participation over the centuries.

To understand the wage gap between men and women after the birth of the first child, there is perhaps nothing more eloquent than this picture:

…

The “guilt gap” reflects a systemic failure. What many women feel and what many men do not feel has to do with the way a society is structured. One way to change the structural is to push from the individual. That is why I insist.

To promote a culture that recognizes that family care and self-care are equally important as paid work, we first have to understand it. Perhaps one of the ways is to experience it on our own skin: to submit ourselves to the process, to roll up our sleeves and do all the things we never did.

Nobody asked me, but here's a recommendation: don't wait for the short circuit or for your partner to explode because he/she can't take it anymore. Get ahead of the process so that it doesn't happen.

Maybe it is shameless and even unfair, but I have an opinion that is also a request: in this dynamic, it is essential that women, somehow, take a step back and not do what they have always done “because the other one won't do it” (well or so well). Come on, go for it, don't do it yourself.

Conflict will arise, we will try, some things will go wrong, we will make mistakes, but we will learn. And you will walk lighter. I know it is not easy and the situation does not help.

I understand that it is not just taking a little side step. It is a deeper process, of letting the other be and of feeling the panic that the world is going to collapse if you don't do what someone else has to do (and sometimes it seems that we will never do).

In all of this, there is a power dynamic that is structural. Men get paid more and that reinforces hierarchies and established roles. So, it is in the home and care where women have more “power” with decisions, information, etc., and without that, nothing works. Neither your home, nor your neighborhood, nor the world.

It's also not that easy to let things go, but it's worth it. By recognizing and communicating that it is hard for you to stop doing something, maybe you can let go of the internalized guilt, or let go of the mental burden of a process that you had made your own. Once everything becomes visible, the processes can even out. Maybe the world will fall apart for a while, and then we will have no choice but to react.

…

This is us for now.

Thank you very much to those who keep sharing this newsletter, subscribing and writing to me (you can always do it by answering this mail, I answer everything!).

I love it when you send me suggestions or complete, criticize or correct some idea. I also love it when you share your own experiences. From the bottom of my heart, thank you so much.

You can find the archive of all the past editions of Recalculating here.

If you want to give me a hand, it helps me a lot if you “like” the publication (it's the little heart that appears there) or if you share it with someone (a thousand thanks to all of you who have been doing it! 😉).

You can also post it on social networks and follow me on Twitter (@pereyranacho), Instagram (@nachopereyra23) or Facebook (Nacho Pereyra).

With love,

Nacho

🙏 Many thanks to Worldcrunch for translating and editing this newsletter.

Before on Recalculating:

Focusing on what’s most important

We had planned last Saturday well: once the two children were asleep, I would leave them with the nanny and go to Athens to meet Irene, who was there for a journalism conference. What could go wrong? Everything that was not in the plans.