The intensity of the present continuous

We’re not exaggerating, we’re fathering. Moments of terrifying anxiety and – spoiler, because we don’t need suspense — a happy ending.

In less than three months, we had two traumatic episodes with my youngest son, León, who’s now two. They’re just stories now, but they were living nightmares at the time. There are some things which bother parents and which can seem like exaggerations for those who don’t, won’t or can’t have children — or who are now way past the baby phase.

Maybe it’s to do with the intensity of parenting as a present continuous with omnipresent alarms which are hard to manage, maybe making it harder to understand from outside — or not to underestimate them.

In March I was in New York for a scholarship from the Dart Center about carers and early childhood. In this monstrous city, which much of society fantasizes about, my main focus didn’t change: my worries, the topics of conversation and my job continuing to be my two children. It’s not that I don’t like travelling or discovering places: it’s that my energy continues to be focused on the titanic task of raising children in their first years of life.

I met a journalist friend from India, Tanmoy, in New York. The topic of our children came up spontaneously, as one would talk about the weather in the elevator to avoid the silence. I told Tanmoy that five-year-old Lorenzo used to eat everything until the age of two, but now was more selective, wanting only plain pasta or rice with olive oil and parmesan cheese.

Tanmoy was quiet for a moment. I was going to ask him if I was boring him, when he smiled and said: “Wow, it’s such a relief to hear that. A few weeks ago the paediatrician told me that my son had lost a kilo and a half. I am so happy that we are talking about this, because I feel less alone.”

We talked about the sensation which torments all parents: the feeling that we’re always doing something wrong. We talked about how hard it is for men who are raising children, because we feel like we are lacking a support network. Plus, we’re a generation which grew up watching stories on the TV of absent fathers or men as caricatures, incapable of looking after babies.

While mothers can perhaps access it more regularly, fathers lack spaces of conversation where they can have a back and forth about the everyday reality of childhood, and share doubts, from “Your son complains about everything too?”, to “How do you plan your holidays?”

But there are others too: “When do you speak about sex with a child?” Or “What do you do when they start drinking and have easy access to drugs?” Or venting: “What do you do when you simply cannot bear your kids anymore?”

It’s not that fathers cannot talk about these things, it’s just that it’s not as natural as talking about politics, sports or women. My friend Tanmoy made a timely observation: “I feel really alone with this whole dad thing. It’s as if only women can talk about their kids. So I don’t know where I stand. Of course it’s more their thing because they’re more involved in raising kids. But what happens to us, the guys that are learning how to care for them?”

…

Things at home go something like this. Lorenzo is five now, so the dangers awaiting him are far removed from what León, my youngest, is at the very real risk of — of something serious happening to him. It’s to do with his age and his character — and no, I am not coming off as an exaggerating, controlling father here.

I say this because too many times I’ve worried about things which have felt exaggerated, but then something happens and I learn: no, that was bad. This realization has come to me two times in less than three months.

The first time was during that trip to New York. I was in the bathroom with León, who was wandering around, from one side of the room to the other. Logical, he is discovering the world.

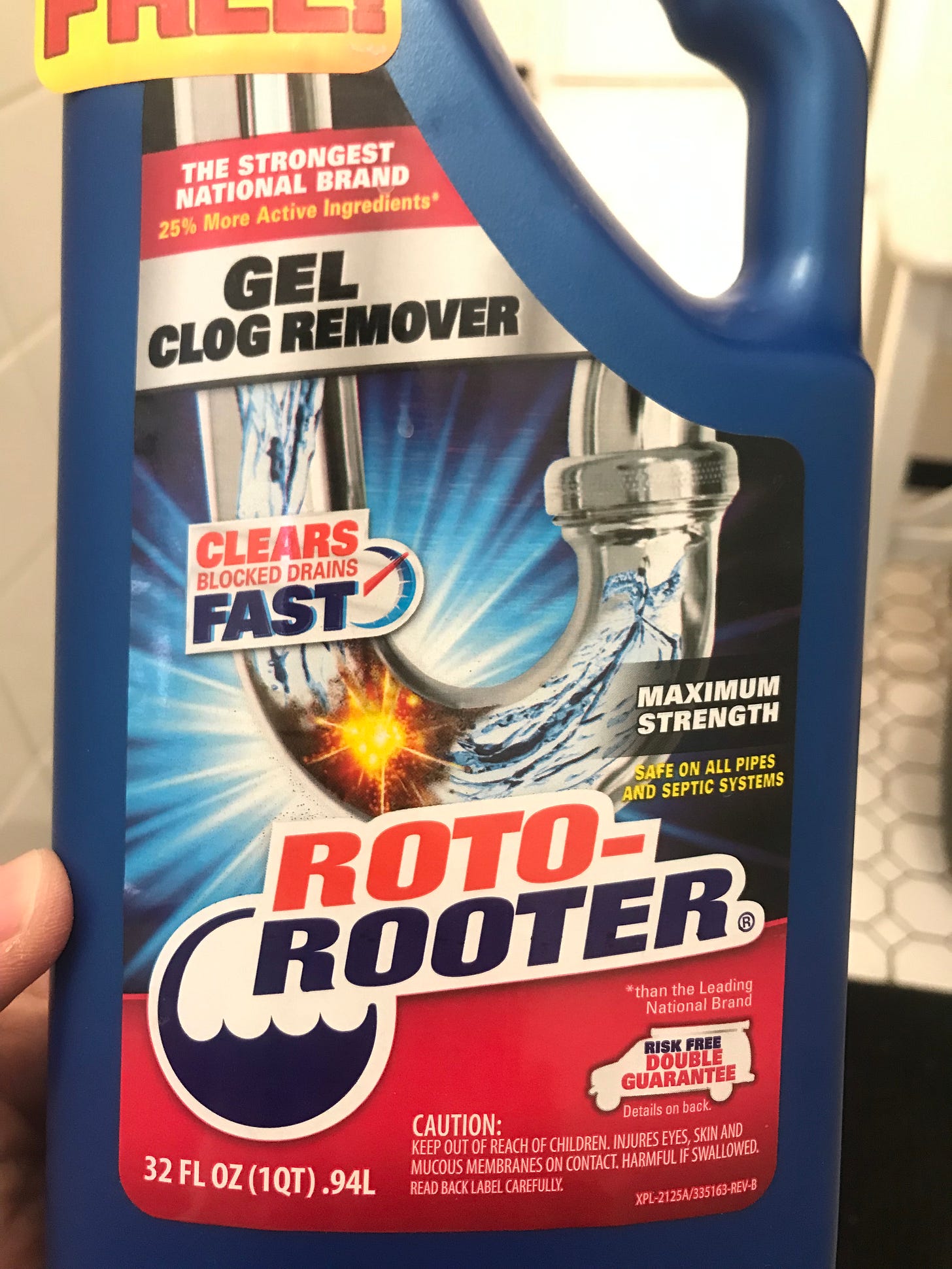

I hadn’t realised he had grabbed a bottle of drain cleaner until it had happened. Before I went to pee, I saw the cap of the bottle spinning the way it does when it is tightly closed; the way they do on the safety lock, when the button just clicks and keeps going around. And I relaxed instead of acting on instinct.

I went about my business on the toilet, when I heard a shriek ten seconds later. I spun around, and León’s mouth was wet, red, the same colour as the t-shirt he was wearing. He had opened the bottle, and he had drunk the liquid. I couldn’t say how much. He let out a heartbreaking cry.

Never mind what went into his stomach — had he burned his eyes and skin? I froze. Instinctively, I put his head beneath running water. Thank god I had help nearby. I carried on washing him with water, and he drank a lot of it. At the paediatrician, we were told we had done the right thing in reaction, and that there had been no reason to force him to vomit, but that if he vomited of his own accord, that was good — and that was what happened.

After an hour of crying, of stress, León calmed down. He played for a little while, and fell asleep. He awoke full of energy, ready for the day. As well as the feeling of guilt, I was still in a state of terror, because I had no idea what was happening in his stomach. And in the end, he was fine.

Maybe it seems like a minor incident, because it turned out well. But for a father, at least for me, that moment of panic in which you are suddenly, shockingly reminded of the fragility of life (of your child) became a stress which buried deep inside me, an alarm which reminds you that in this phase of their lives, children overwhelmingly need you to survive. When they are so small, danger lurks in every corner.

…

The other nightmare started in the middle of June and lasted for three days in the children’s hospital of Athens.

It all began on a Friday. We were eating pistachios with Lorenzo. León wanted some too, and so I put one in his mouth, split in half, very intentionally and carefully, knowing of the risks that eating solids in general can present — and knowing how much more dangerous it is to be moving while eating, and not sitting.

And then León, chewing away, decided to stand up on his high chair and jump towards me — it all happened very quickly. I caught him, his feet in the air. With the jump and the sharp catch, the food went everywhere. He started choking. His face turned red, there was no sound, he was not breathing. He was suffocating.

It was horrible.

Thank god Irene was there. We attempted the Heimlich maneuver. I cannot describe the fear in those, how long was it? 10 or 20 seconds? in which León was not breathing. It felt like hours. And suddenly, he coughed and spat. Terror. I turn into jelly just thinking of it.

Could he have died? asked Lorenzo, as León carried on crying and coughing.

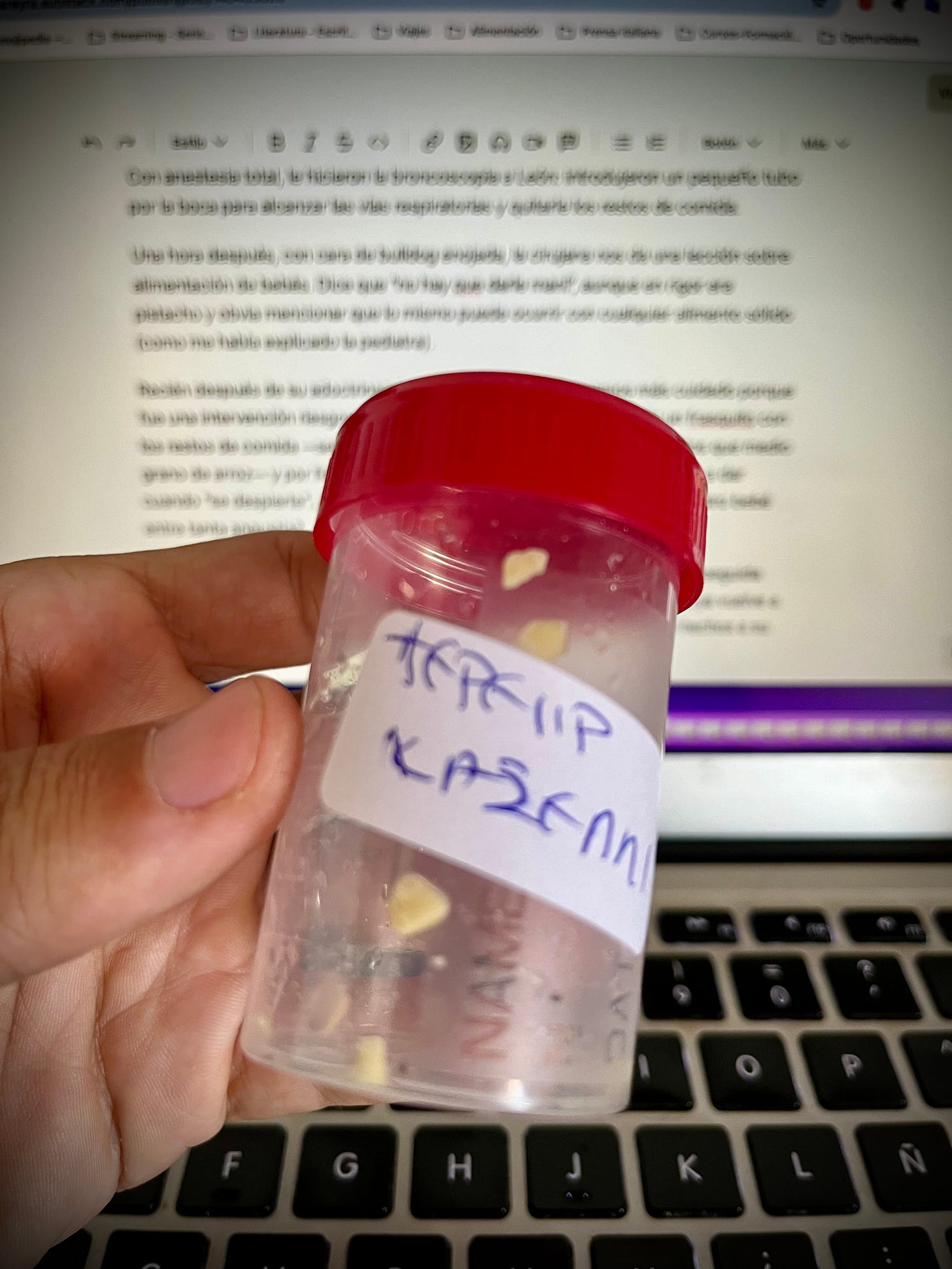

His cough continued for a couple of days. We feared a pulmonary infection and took him to the doctor, explaining what had happened that Friday. “He could have food in his lungs,” said the pediatrician before even checking him, and sent us straight to the ER.

We got to the hospital at 8:30 pm on Wednesday night, and left on Friday at 2 in the afternoon. Two eternal nights. He was on saline for the first 15 hours — they had to pinch five times to find his veins — he was not allowed to eat or drink to ensure a bronchoscopy and to extract whatever food was in his lungs still. León, at 20 months, was never going to understand why no one was responding to his desperate pleas for water and food. Disconsolate, stressed, he slept only four hours instead of his usual 11.

On the second day, we were finally able to take him to the operating room. The anaesthetist took him as if she was picking up a package and the only thing we heard was a cry which continued until it died away. We heard nothing more for an hour.

In her own newsletter post about this, Irene wrote:

“When they take León away from my arms, screaming, to take him for his anesthesia, my heart breaks. I burst into tears. No rational thought can soothe me. Nacho and I hold each other’s hands, and we hardly speak.

We both fear the worst — and I fear for León without us next to him.”

Under total anesthetic, they did the bronchoscopy, inserting a small tube through the mouth to clean out the airways and get rid of any remaining food. An hour later, with the face of a raging bulldog, the surgeon proceeded to lecture us on how to feed children. “No peanuts”, though it was pistachios or could honestly have been any other kind of solid (as the doctor had told us before we came to the hospital).

Only after the lecture, and to warn us again to be more careful because this had been such a tricky procedure for someone of León’s age, did the surgeon hand over the fragment of food they had extracted — six little pieces of pistachio, smaller than rice grains — and finally let us know that León “was fine”, that we would see him when “was awake”. Amidst such angst, did we have to wait so long to find out that our baby was ok?

Back at home, where the nanny was, Lorenzo was asleep in our bed. He heard me coming, and asked: “Is León ok?” Yes, León is fine, we just had a scare, he will be home tomorrow. I explained it simply, an attempt to adapt the facts to his age and level of understanding. Months later, all of this — the bleach, the pistachios, the operating room — all seems like little stories from the past, although the memory of them is enough to overpower me with grief.

I felt this grief subside over the next few days, as we got back to normal, how it became an elastic, imprecise matter thanks to the conversations we had about those incidents with friends, which helped me to process what had happened and elaborate on those events, to tease out the rationale and speculate. To take, to relieve myself of the burden, to share my fears and doubts. To reflect. I suppose, as I was talking to my friend Pablo, that these too are tests that we have to go through as parents, as well as children, so that all of this energy goes somewhere, educates us, calms us, and later transforms us.

This is us for now. Thank you very much to those who keep sharing this newsletter, subscribing and writing to me (you can always do it by answering this mail, I answer everything!).

I love it when you send me suggestions or complete, criticize or correct some idea. I also love it when you share your own experiences. From the bottom of my heart, thank you so much.

You can find the archive of all the past editions of Recalculating here.

If you want to give me a hand, it helps me a lot if you “like” the publication (it's the little heart that appears there) or if you share it with someone (a thousand thanks to all of you who have been doing it! 😉).

You can also post it on social networks and follow me on Twitter (@pereyranacho), Instagram (@nachopereyra23) or Facebook (Nacho Pereyra).

With love,

Nacho

🙏 Many thanks to Worldcrunch for translating and editing this newsletter.

Before on Recalculating:

Grandparenthood

Sometimes I wonder if I will have grandchildren, and if so, whether I will get to know them. But more often, I feel sadness, frustration, and helplessness knowing that León and Lorenzo will never meet my parents, their Argentine abuelos.