Refusing to be desensitized

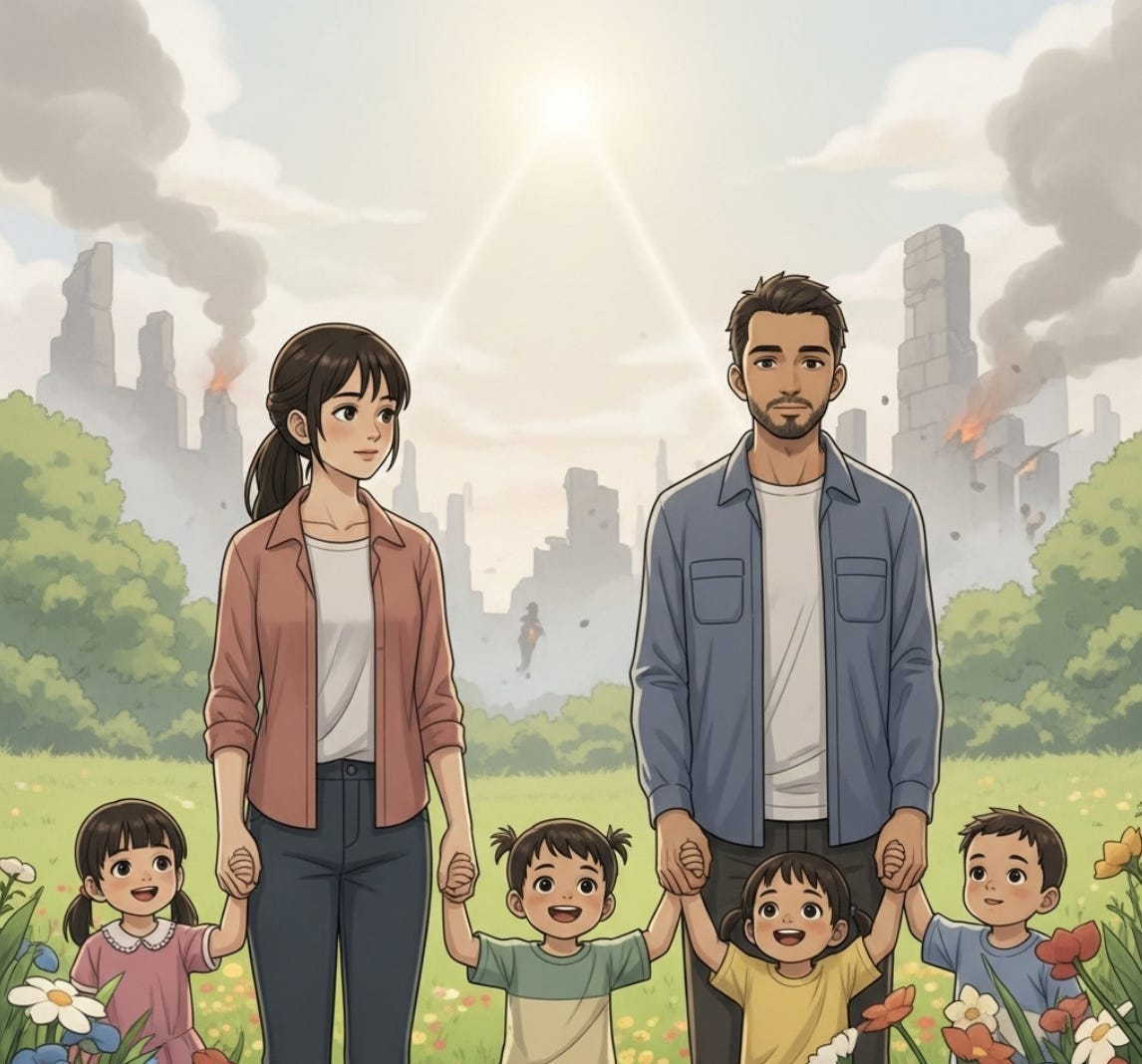

Parenting in a world in crisis. The dissonance between intimate and global. Daily resilience facing hyper-normalized chaos. The idea of heroism as the horizon of fatherhood is unbearable.

It’s quite emotional seeing how the milestones creep up on you. Lorenzo finished pre-school a couple of weeks ago. In September, he starts first grade. This time though, I was struck more by León’s end of year preschool play.

It’s not about the boys per se, but about me, as it is with much of fatherhood. The questions that I ask myself. Should I write about fatherhood in a world which seems to be collapsing? Is it better to focus on the dissonance between the intimate and the global? I’ll try and speak to both things, with some digressions.

Let’s begin with the end-of-year play. León crawls on to the stage against the soundtrack of To the Moon and Back. To my surprise, I catch myself crying for the entire three minutes he’s on. Where did these tears come from? What triggered them and what spaces did they open up?

One of the triggers was obvious. A child with his parents in the row in front, shouting “Granddad, Grandma! here! here!”, calling them over to sit with them. My late parents will never know my children. It’s emotionally obvious, and it doesn’t make it any less real.

I had also been following the news more closely. Wars, missiles, conflicts. Deaths, many deaths. Images and videos of babies and children dead, bloody. What do you do with all of this anxiety? It’s horrible to look at the reality, especially when you’re doing it out of the corner of your eye or mindlessly scrolling on the sofa, or on the beach.

I thought of León’s innocence and luck being on that stage. It pierces my heart to think of other children like him, or younger, crawling through the dust of the ruins created by the bombs which keep exploding on them, around them, killing them every day.

Babies and children assassinated every day, killed with their friends, parents and siblings, for an unhinged battle for power, land and geopolitical madness where the chaos masters are plunging the world into a spiral of conflicts.

Try and talk about war with a child and tell me how the absurd attempt of explaining so much stupidity and folly feels.

It’s night when we come home. Lorenzo says he is afraid of robbers grabbing him from behind. If he looks back, he is worried they will appear from the front. He feels there is no escape: that no matter where he looks, there is this possibility in his little head that a robber will appear and take from him, take him. Where does this fear come from?

The nanny was ill for a week, and so was León, so Irene and I looked after him. “The mystery of life is not a problem to be solved; it is a reality to be experienced,” said Kierkegaard.

I guess my children see it in much the same way. They don’t think about the obstacles they have to overcome, but they live with the continuous experience of learning, losses and joys. They’re discovering the world every day.

Lorenzo is happy at the summer camp, a new place with children he does not yet know. “I like it more than kindergarten,” he said. “I made a friend on my first day. We were playing all day.” It’s something that we all need to do more: meet up in person, play, connect. At least, those of us who can.

I saw a post on Instagram where a father is juggling triplets and a small girl. He attaches a wooden plank to a cot on wheels which he maybe custom built to fit their four small bikes and water bottles.

The spirit of the post and the comments under it celebrate this heroic man (who “looks for great solutions to great problems”). The epic as a horizon of fatherhood. Insufferable.

I commented on the post: “It would be good to ask ourselves why an adult ends up in charge of four children? In social and structural terms, what does this say?” The replies were that they saw a father looking after these four because it was his duty.

One woman set another two straight: “He’s not talking about father or mother. You always come out with the same thing… These can be children of another father too. The comment is about an ADULT… I fear how quick you are to defend the supposed mother…”

In any case, the post makes me think of the limitations of the nuclear family, the isolation and the loneliness of those who have or care for children, and the lack of care networks. Four children (especially three very small ones) is a LOT for a sole adult. It’s something symbolic which speaks of the structures of how we care for ourselves and raise others, and what we prioritise.

I see a trap in this time which marries loneliness, isolation, the nuclear family and the celebration of a supposed superpower of managing four children. It can make us think that raising children is an individual pursuit, one of overcoming one’s self, and not of the collective.

In the video at one point, a baby who is on the road, crawls down there. We don’t know how long for nor how many times this happened because the video is edited. What would those who celebrate this video and see its protagonist as a hero say if something had happened to the baby?

I spend a bunch of time with my two children out onto the streets and I can affirm that the risks are very present. Today, for example, I stopped to drop Lorenzo at summer camp, and I had walked some 50 metres away from the car when León decided to unbuckle his safety seat and open the car door.

León is two and a half years old and can’t get out of the car onto a street with minibuses, motorbikes and cars. I ran, yelled and arrived before he managed to get out. Very little needs to happen for my boys to get hurt. I am not saying this to stoke far — I’ve spent the past six years with my children travelling around the world — but I speak from the experience of having been to the hospital far too many times and having too many scares. I also know that many parents, without help, prefer to stay at home rather than go out with their children.

Crude duality

All these complaints are quite ridiculous in many ways. My children are alive, they’re not dying, nor are they dodging bullets or tanks of war. It’s a parallel reality which sets me worlds apart, but it hurts nonetheless.

I read about bombed and destroyed hospitals, about people murdered while they queue for food to not die of starvation. One click later, and I am following Lionel Messi’s games, replaying goals from the FIFA Club World Cup and paying for another week of Lorenzo’s summer camp. It’s a cruel duality.

Disaster is being normalised, like a film which makes us sad but in the end finishes and we turn it off and carry on with our lives. This, we follow. “The World is Burning but I’m Still Getting Slack Notifications,” as said in a recent newsletter post by US journalist

. In it, she describes feeling like she lives in two completely unrelated worlds.In one world, she goes about her life, confirming meetings, making projections for the next quarter which might not come, and reads about which yoghurt to buy. In the other world, (yet another) war is declared, and its importance is immediately undermined. “We’re being lied to about its causes, just like we were lied to about the last one, and the one before that,” she writes.

Reality can be frightening, but we carry on. Plank shares an insight from psychology, which intimates that what can seem like numbness — refreshing an inbox while the world is falling apart — is actually a type of resilience.

Plank writes: “Not the heroic, cinematic kind, but the everyday kind that quietly insists on continuing. It’s built on emotional flexibility, community, the stubborn human need to make meaning even when everything feels meaningless. And while it doesn’t look like resistance in the traditional sense, maybe that’s what makes it powerful. Maybe the real rebellion is just… refusing to go numb. Refusing to stop noticing. Refusing to stop caring.”

In another post, Brazilian futurist Daniela Klaiman asks: “How do you describe this feeling that everything is bad, but at the same time, the world acts as if everything is normal? They say that the word we are looking for could be ‘hypernormalization.”

This term describes life in a society whose institutions are decaying, where there are wars and global conflicts, extreme climate events which are becoming routine, humanitarian crises which are intensifying. Nonetheless, everything looks like just another average day.

“The danger of dysfunction is that we simply learn to live with it,” warns Klaiman in Portuguese in a post on LinkedIn. “But understanding the concept of hypernormalization gives us the language, and the permission, to recognise when systems are failing, and clarity about the risk of not acting while it's still possible.”

A collective wellbeing

I’m driving back from dropping the youngest at kindergarten, and I get stuck at a traffic light. I fear I am going to be stuck in this traffic jam, but a guy in a red car puts a hand up and lets me pass.

I feel desperately grateful, and so I raise my hand in thanks. Did he see me? To be sure, I stick my hand out of the window, thumbs up. I am smiling. The guy drives past, lowers his window, honks in greeting and smiles.

For a moment there, I felt like both of us generated a feeling of joy or wellbeing in the other which only depended on us. Maybe we lead shitty lives, who knows, but if we all shared more moments like this, moments which are as contagious as the downers and bad moods, I am sure we can create bubbles which — and sorry for my Little Prince style innocence — create better moments for everyone.

It sounds naive, but I’ll say it anyway: we can be stronger together in a collective, down to just a smile from far away. It’s not one thing or another, you see. In life, in relationships, and in the world, there’s a whole that needs to be integrated.

Living comes with enjoyment, with the smiles of our children and with the wise choice (or not), but it also comes with injustice and the madness of each era. We don't have to ignore or stop caring about what's going on. We can refuse to be desensitized.

That’s it for today. Thank you very much to those who keep sharing this newsletter, subscribing and writing to me (you can always do it by answering this mail, I answer everything!).

I love it when you send me suggestions or complete, criticize or correct some idea. I also love it when you share your own experiences. From the bottom of my heart, thank you so much.

You can find the archive of all the past editions of Recalculating here.

If you want to give me a hand, it helps me a lot if you “like” the publication (it's the little heart that appears there) or if you share it with someone (a thousand thanks to all of you who have been doing it! 😉).

You can also post it on social networks and follow me on Instagram (@nachopereyra23), Twitter (@pereyranacho) or Facebook (Nacho Pereyra).

With love,

Nacho

🙏 Many thanks to Worldcrunch for translating and editing this newsletter.

Before on Recalculating:

Exhausted Mothers, Lost Fathers: The Crisis No One Talks About

Sometimes, men and women seem like two neighboring worlds divided by glass: we can see each other, but not really hear what’s on the other side. It’s a disconnect that breeds helplessness and turns proximity into misunderstanding — even when we're standing face to face.