Between my notes app and my armour

A glance through the archive of my notes provides an echo of the pressures I am under; of questions asked impertinently, where is the mother? And of identity, fragility and resistance, amongst others.

The posts on my notes app on my phone are anarchic. I keep notes enthusiastically. Then, on rereading some, I see that they read like nonsense. Sometimes, I want to engage with what I have written. These are just my banal daily thoughts, which show the tensions, cultural pressures which affect us, reports on how we’re doing with our health (and emotions), and the importance of empathy, vulnerability and human relations.

All of my notes come from something I have read and link off to those places, except for the very first one which I wrote more than five years ago, like a diary, before I started publishing Recalculating.

Where is the mother? (August 2019)

Parking in Italy is a hassle, but I find a spot. I sense an uncomfortable morning ahead of me, once again being in places which were not expecting me. Lorenzo is six months old, and he is up for his third polio shot.

I don’t need to have picked Lorenzo up to realise what I spotted two minutes ago in my windscreen mirror. That unmistakable grimace, lips pursed and cheeks reddening from the endeavour, it’s that unambiguous tell: he has pooped.

Where should I change him? In the hospital cafeteria, I ask for a bathroom with a changing table. There, at the front. And I see it for what it is, yet again: ‘women’s bathroom’.

Why? In a flash of provocation, I decide to change Lorenzo on a table. Will someone say something to me?

We head up to the first floor and wait for the pediatrician. In the waiting room, I present Lorenzo’s vaccination card. “It’s time for his polio shot, right?” I ask. The doctor seems uneasy. She looks at me, checks the document, and looks at me again.

“Is something wrong?” I ask.

“And the mother? Where is the mother?”

“Working… why?”

Reading too many women writers

Since I began writing, and especially since I began publishing and speaking publicly about my readings, a series of friends, colleagues, journalists, critics have asked me the same question: why do you read so many women writers? It’s a question which I always find perturbing, never mind in replying to, which I do evasively, with subterfuge. It’s almost as if telling the truth — which I myself was barely aware of, since I hadn’t discussed it — could expose me to the worst danger.

This is how a post (in Spanish) by Argentine writer Leopoldo Brizuela begins, published in 2014 in a blog hosted by the Eterna Cadencia bookshop in Buenos Aires (and which my friend Cecilia sent to me). The writer reflects on a recurring question — why he reads so many women — and how this line of query revealed a deep cultural bias.

Brizuela explores the construction of masculinity in patriarchal societies, where men distance themselves from the feminine in its identitarian form, perpetuating dynamics of exclusion and symbolic violence. He maintains that reading women writers has been a path of resistance and self-discovery for those who have been left in the margins of hegemonic masculinity.

“Reading women was a way of transforming our homeric burdens of pain, hate and violence contained in a new and alternative productive force,” writes Brizuela, who criticises how the literary camp reproduces masculine power structures.

Women get pregnant, men get injured

In a Spanish-speaking Youtube interview last year, chef, entrepreneur and activist Narda Lepes and her accountant analysed the data behind time signed off work in her gastronomic undertakings in her native Argentina.

The head of Narda Comedor (which ranks as one of the 50 Best Restaurants of Latin America) found that 70% of those had been granted to men; 85% of those were for injuries incurred while playing football. In contrast, 80% of absence notes put in by women were to take time off to take care of someone.

“Priorities, right?” said Lepes, highlighting the discrepancy between motives and absences. She also questioned the argument that hiring women is more costly because of maternity: “You have those who say, no, because they get pregnant. The costly thing in my professional life is actually those guys and their football injuries”.

Her comment went viral and lit up the social media networks: “Will they start asking men in interviews if they play football, just like they ask us women if we’re going to have kids?” (from an association looking at gender-based violence, ‘Ahora Que Sí Nos Ven’).

The writer and journalist Mercedes Funes did a deep dive into this and found that, according to the Argentine National Time Use Survey (Encuesta Nacional del Uso de Tiempo, or ENUT), women spend around 6.5 hours a day tending to care activities, while for men the figure is 3.5 hours. The gap is still big, even though men are increasingly taking part in household chores, especially those men who are separated.

What remains of memory?

“These are recurring themes for me: what children register, what I registered when I was a kid, what is being etched in my kids’ memories now,” writes Argentine journalist

in his newsletter. Anyone with children can testify, I think…What I learned as my kid’s football trainer

The U.S. journalist Rory Smith has spent 40 years watching football. But it took three months of training a team of under-7s — including his young son — to have a revelation.

“There is something, about seeing your child play — knowing their happiness is dependent, to some extent, on the outcome; knowing that you want them only to experience pleasure, and never pain; knowing that you are all but powerless to determine what happens — that sharpens the senses,” he writes.

“Perhaps that stands to reason. Perhaps that is something people have always known, that it is in sports that parents catch their first, unnerving glimpse of what is to come: a son or daughter, out there in the world, no longer under their protection, reliant only on themselves and their friends to overcome the challenges being placed relentlessly in their path.”

Suits of armour

Last year Challengers came out, a dramatic comedy set in the world of championship tennis, directed by the Italian Luca Guadagnino. He is a cult figure because of his Tilda Swinton vehicle I Am Love (2009) and Call Me By Your Name (2017). In a (paywalled) interview for a Spanish newspaper he explained what it was he found in tennis: “A form of control of oneself which seems very violent to me,” he was quoted as saying. “And also something familiar, which is the way in which people build suits of armour to reach their goals, and to hide the goals which they want to reach.”

Hurt, hurt again, hurt better

From Nick Cave’s newsletter, he speaks about how he disagrees that it should be painful to remember “amazing times” of the past, since there is so much more to come. He says there will be more broken hearts, but those hearts will break more deeply:

“We must not retreat from our feelings. We must confront them. Rehearse them. Get better at them. To paraphrase Samuel Beckett – hurt, hurt again, hurt better.”

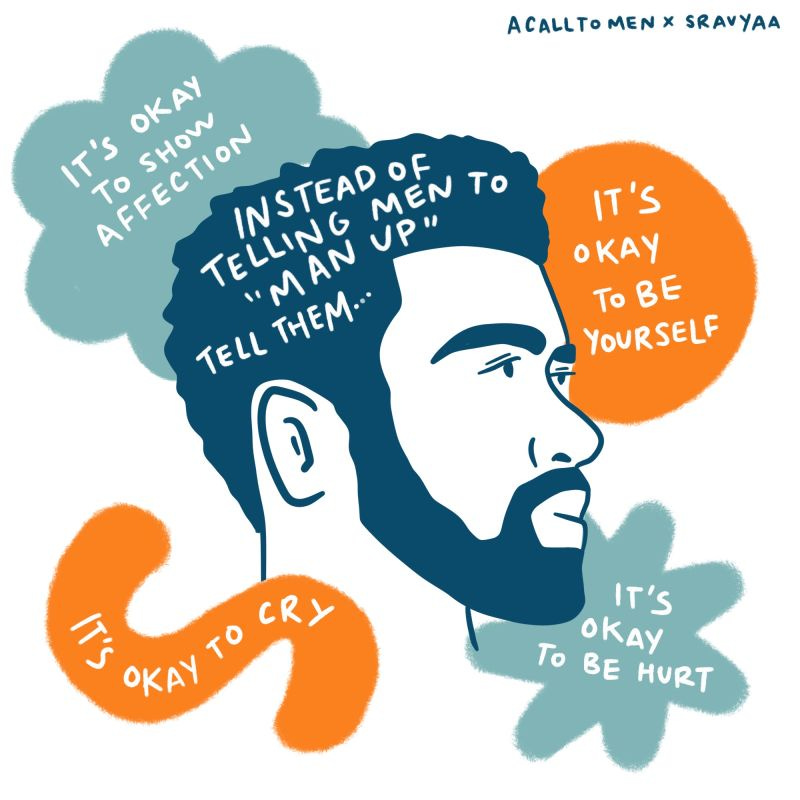

Machos and health

The ideal of the macho guy is negatively impacting cardiovascular health, according to a recent study reported in Spanish daily El País. A study warns that men tend to act in line with gender stereotypes — aka hiding their results and treatments — when it comes to managing health issues such as hypertension.

What really matters

I don’t find it easy to cry, and I admit that it’s one of my defects. But this piece by U.S. writer

did make me cry. Fay reflects on how, at the end of life, what matters is not material successes or appearances, but the impact we have had on others. Love, wellbeing and genuine connections are the things that leave a mark.It sounds like a cliché, but Fay movingly describes how her mother, in her last moments of Alzheimer’s, showed love and gratitude for her carers. She writes clearly about what remains is kindness and generosity towards others.

“I’ve never been around someone who was dying. I’ve never really been around death. Now, I’ve experienced both,” the article from her newsletter begins. I was moved because I had flashbacks to my own parents’ stories. They have both been gone for over a decade. I thought too about people that I love who have difficult relationships with their parents. Though they didn’t ask me to, I would maybe ask them if they had ever thought of spending time with their parents before they are gone.

That’s it for today. Thank you very much to those who keep sharing this newsletter, subscribing and writing to me (you can always do it by answering this mail, I answer everything!).

I love it when you send me suggestions or complete, criticize or correct some idea. I also love it when you share your own experiences. From the bottom of my heart, thank you so much.

You can find the archive of all the past editions of Recalculating here.

If you want to give me a hand, it helps me a lot if you “like” the publication (it’s the little heart that appears there) or if you share it with someone (a thousand thanks to all of you who have been doing it! 😉).

You can also post it on social networks and follow me on Instagram (@nachopereyra23), Twitter (@pereyranacho) or Facebook (Nacho Pereyra).

With love,

Nacho

🙏 Many thanks to Worldcrunch for translating and editing this newsletter.

Before on Recalculating:

Stars above, memories below

Over the past couple of days, two anniversaries have overlapped: my mother’s 85th birthday and the 13 years since my father’s last breath. Some days I forget they’re gone and think of them as if I could still drop by and visit. It isn’t sadness or nostalgia — it just is.