When A Baby Is Born, So Is A Father

Thoughts and surprises from a week of caring for two children. Readings: "Birth of a parent". And a beautiful photography project.

I spent a week solo-parenting my two children while Irene, my partner, was away on business. There were moments of anxiety, when the accumulation of fatigue took its toll: my patience was squeezed to unknown limits. But everything turned out much better than I had feared before Irene left.

At 17 months, León spent his first day without his mother (and his second, and third… for a total of seven nights!). And for the first time he also didn't have his teta — he did not breastfeed — and breastfeeding was always a great ally, especially in times of crisis.

The truth is that we men are not usually left alone to take care of our youngest children for "so much" time. I put "so much" in quotation marks because one week is a ridiculously small amount compared to the time women spend with their children compared to men.

A little bit to encourage me, but also to help me readjust my perspective, a journalist colleague told me that she left her career aside when her daughter was born — as so many women do — and that only now, nine years later, she was able to go back to it (and she was happy about it).

During that time, this colleague told me, it was difficult to postpone her projects, but she was also happy to have been able to see her daughter's growth from up close. I recognized myself very much in these mixed feelings.

In these five years that I have been a father, my main task has been to dedicate myself to the children and the housework. In some periods we had some help and I worked on projects to earn money. But they were always freelance jobs with a lot of flexibility.

These years have been flourishing and full of life, but they have also been very hard at times. Exhausting too — physically, mentally and psychologically. This is partly because I was socialized to be a productive man, and working is what I did sporadically from the age of 15, and then non-stop from the age of 17 to maintain the life I chose.

Doing what women have always done — raising, caring, running a household — is a universe of discoveries and permanent challenges. It helps me better understand their struggles and also get a better sense of my mum’s experience — she raised seven children and never stopped working (both at home and as an architect).

It's also a way to discover aspects of my personality that I would never have known. And to ask myself questions that I would not have asked myself if it were not for the experience of exercising parenthood in such a close way. For example: can I feel fulfilled if I don't work to earn money?

This week in particular was a challenging one: how would León, a baby who has never had a bottle or used a pacifier, react to sleeping without breastfeeding? What would happen to Lorenzo, at five years old, when he saw that I would put León to sleep first, when I have been reading to him and accompanying him to sleep for three years, while Irene was with León?

One can try to plan, but then life follows its own course. León would spend up to an hour and a half nursing before falling asleep. My fear — both for my mental health and for my lower back — was having to walk him around in my arms all that time.

In the end, all week he simply sat on the bed to put on his pajamas and then hugged me and fell asleep, most of the time without me even having to walk. I will never forget these nights when he fell asleep like that — his head settled on my shoulder, his arms around my neck, in a tight hug.

It would have been more than a shame if I had missed these days with León, just as it would have been a shame to miss the last three years talking and reading with Lorenzo during bedtime. I think of that with gratitude and as a balm on tired days.

Being present as parents is an effort. It didn't come naturally to me, but our life as a couple put me there, and I accepted it; then came the rest. I think it is an effort mainly because I am learning all the time, while at the same time making a lot of mistakes. That has never happened to me at work, where the pace is challenging but there are long stretches of time when you have mastered your skills, when you can navigate with your eyes shut, knowing exactly when to pick up the pace and when to drop anchor.

Parenthood is unpredictable, like permanently navigating in new waters. From one moment to the next, the sea can get rough — and there can even be a storm and sunshine at the same time.

Michael Feigelson, CEO of the Van Leer Foundation, which focuses on early childhood and caregivers, is right when he says that “when a baby is born, a parent is also born”. He dedicated an article to the topic, wondering what would happen if we looked at the early years of parenthood in a similar way to how we look at early childhood:

“A period of five years in which every dimension of our identity undergoes a metamorphosis. Our brains and bodies soften and reorganise. We learn and adapt with exceptional speed. Our web of social relationships transforms. We experience feelings for which we need new words that we struggle to pronounce. Our days and nights are in equal part awe and exhaustion. What if we agreed that when a baby is born, a parent is also born?”

In the same magazine, the 2023 edition of Early Childhood Matters, there is an interview with Colombian singer Juanes. He says that when his third child was born, he decided to take time off work: “When Dante was born in 2009, I couldn’t handle the pain I felt and his crying when I left home. It was devastating because the same thing happened with Luna and Paloma. At that time, I realised that I had lost a lot of time without making a space where I could look after myself.”

We are talking about a hyper-privileged guy — white, millionaire, successful. But what happened to him is not much different than to what happens to the rest of us mortals, especially when it comes to the reactions around him.

“It was pretty strange at that moment. They thought I was crazy. Why would I want to stop earning so much money and abandon a very successful streak? But I made the right decision. I only took a break of four or five months, but that was what I needed,” Juanes said in the interview.

Why do you think that it is so hard for us to make that type of decision as fathers?

We are educated in a society where you always need to be producing, but our children and our relationship with them is what we need to care about. I was very anxious at that time because it could have been the end of my career, but today, in retrospect, I feel happy because I made a decision that was consistent with who I am.In our work, I’ve seen that, especially for fathers, and men in general, it’s difficult to open up emotionally. Why do you think this happens?

I think that, maybe for the same reason why society demands that we produce more and more, we have also had a macho society in which men can’t cry, can’t show any type of “weakness”. But I think vulnerability makes you strong. Talking with your best friends or people you confide in about your problems at home or with your children can be the healthiest thing you can do.

…

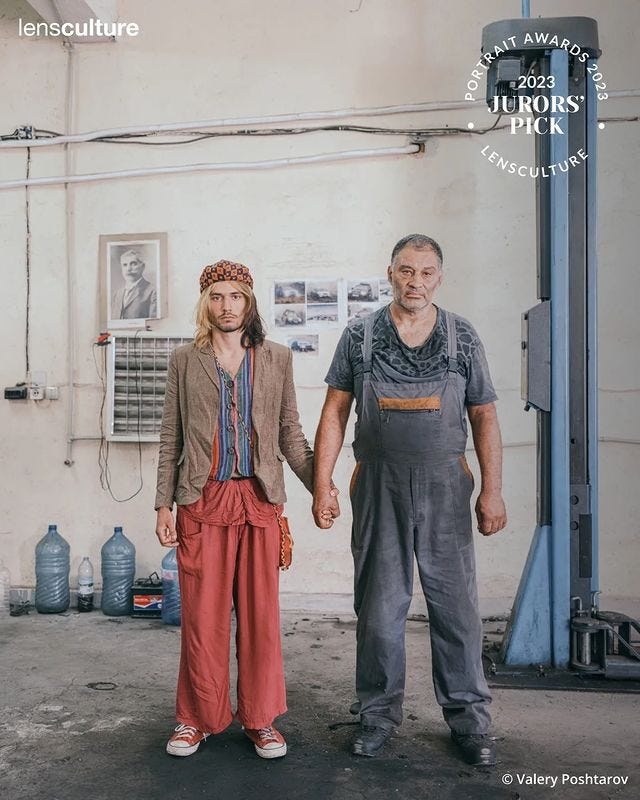

All the photos in this newsletter are from Father and Son, a photo project that my friend Boryana shared (thank you! I love it when readers contribute and improve Recalculating).

It's a simple and powerful idea: Bulgarian photographer Valery Poshtarov takes pictures of fathers and sons holding hands in different countries and cultures. It's a wonderful initiative, considering that the dominant idea of masculinity rejects or, at least, avoids tender physical contact (beyond the tight embrace, with strong pats on the back and making sure there is no accidental touching in the lower parts) and intimacy between men, even if there is a tight bond.

Poshtarov argues that in a world that is already drifting apart, "holding hands becomes a silent prayer, a way of getting back together." The photographer notes that, as they pose, parents and sons hold hands for the first time in years, sometimes decades.

“It's a powerful moment, often filled with hesitation or even resistance, that reveals the universal appeal of connection, legacy, and vulnerability in our human experience. The essence of the project lies in this intimate act, the photos standing as a witness to the profound, yet often unspoken, love between fathers and sons,” he explains.

If I could, I would certainly take a picture holding hands with my dad, as Poshtarov proposes. He died more than a decade ago. Luckily, at least, next to my desk I have a photo with him and my mum, the day I got my diploma as a journalist. Each of us is looking in a different direction but we all share something: we are smiling and hugging each other.

…

Thanks for reading, for sharing Recalculating and for writing to me (you can do so by replying to this email!).

I am very mindful that I still owe answers to several emails from the last few weeks. I will get to them, I promise. And I hope that, in the face of my ungrateful lack of responses, you will not stop writing: I love reading your emails.

With love,

Nacho

…

🙏 Many thanks to Worldcrunch for translating and editing this newsletter.